The Forensic Audit You Must Conduct Before Making New Resolutions

1) Who did it is not the right question

Is a good murder mystery really about who did it? Throughout the story we keep trying to figure out who the culprit is by asking ourselves why each character would have done it? Think about this: If, in the next you read or watch, you are surprised by who and it just ends abruptly, without any hints at why they did it, it will fall flat. We wnat to know why. Any hack writer can invent bad guys that are just born evil, to believable we need to know the deep resentment that fuels their deviance. The real intrigue is in the motive.

The previous post about New Year’s Resolutions determined that last year it was you in the study with the lead pipe. Anyone who has a modicum of personal integrity already knew that. Admitting that is a big part of making progress – a necessary first step. But the game didn’t say why you did it. If you can handle some added suspense in the psychodrama that is your life, try and figure that out. If you do that you have a fighting chance of not becoming a repeat offender and being can be among the top 4%.

2) The top 4%

30% of people make a New Year’s Resolution. 80% of them actually take some action. But less than 20% of them actually see it through. For those who forget how to square the numbers:

0.3 x 0.8 x 0.2 = 0.048, or less than 5%

3) Feel the pain

It’s the time of year to make new resolutions. I could easily jump ahead and make a list of ten things I should start doing and ten things I should stop doing. We all could. I have so much room for improvement that this question is utterly ridiculous. And all ten things that first come to mind are all things that other human beings do or have done, so knowing how is a problem I can resolve. The real question is: Given limited time, resources, and willpower, which should I do and will I actually do?

The obvious answer is something important enough and something within reach. Important brings us back to ‘why?’

“He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.”

Friedrich Nietzsche

To hammer home the wisdom in that short statement, try the opposite; how to change but don’t give a damn why. Motivation matters. If we feel some remorse over not meeting last year’s resolutions it’s because we know at some level that we just didn’t care enough. The words motivate and emotion (and motive as well, for that matter) stem from the Latin word movere – to move. There must be a strong enough emotion to get us to move.

All emotion has a negative or positive valence. Needless to say, negative emotion weighs heavy in the balance. The pain of your finger touching a hot stove will get you to move it lightning fast. A lot faster than if you had it in slowly boiling water. It seems that the meme of the frog in boiling water is not true. The frog will not die with a big smile on its face, it will do exactly what you will – try to get out. But, like us, it can get damn hot before it does. Pain will make us move, but we can get very uncomfortable being uncomfortable.

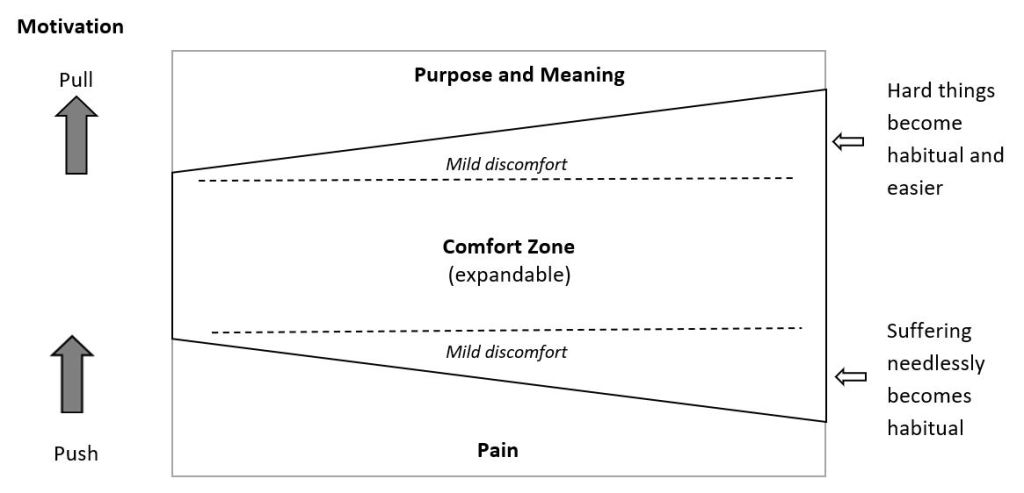

Pain is the ultimate motivator. We either want something so bad it hurts or we are sick and tired of being sick and tired. We can be driven by something pleasurable or meaningful or desperate to ameliorate our situation. The Olympian is a good example of the former – being pulled towards something higher rather than push into action. Love is in this category too. Most resolutions are about fixing a problem. When we wallow in our comfort zone or expanded it, either we weren’t really sick of it or we weren’t that hungry for it. Thus, we don’t just need ask ourselves ‘why’ when we look forward to what to fic, we need to also look back and ask ‘why not?’ – why we didn’t do it.

1) Trick question

We have reasons, perhaps excuses, the mystery gets interesting when we discard those and answer the following question: How am I complicit in creating the conditions I say I don’t want? Jerry Colonna often repeats this phrase that his therapist repeatedly asked him. In a recent podcast with Tim Ferriss they explore that complicit is an ideal word as being fully responsible places an immense burden upon us that may be no more helpful than denying any responsibility. Complicit acknowledges that much of life is random. The nuance allows us to focus on the things that we can control and we can change. He explains:

“I get very, very angry when people misinterpret the word ‘complicit’ for ‘responsible.’ And it’s not because I want to let people off the hook but quite the opposite. I want people to understand that they’ve been an accomplice. When we get into our mindset that says, ‘I am responsible for all the shit in my life,’ we’re actually walking away from doing the hard work.” — Jerry Colonna

Tim and Jerry go on to explore how the real question is buried in the part of the question that gets ignored: “… the conditions I say I don’t want.” The heavy lifting is in figuring out exactly why we aided and abetted the criminal. And so the real mystery is what we really want.

The answer I think the first line of evidence to follow is to take a hard look at what we did do. If we consistently chose something other than the thing we proclaimed was a priority then our values clearly lied elsewhere. Likely in habitual and comfortable tasks. When we incline towards the familiar we create alibis, we feel busy. It lets us off the hook – temporarily.

Recall, the first thing to ask is what is important enough to make it our priority – this is where purpose sits in the diagram above. It resides outside our comfort zone, which is also where our potential sits.

The second line of evidence in this murder mystery is a more difficult one. Look at the flip-slide of our rationalizations and excuses. They allow us to pay lip service to our goals: ‘I would do that, if only….” No wonder that a brutal commitment to truth is hard to cultivate; the lies we tell ourselves don’t just admonish our guilt, they also allow us to feel morally superior.

A powerful clue as to why we might be complicit in letting dreams stay dreams and aspirations remain as good intentions is the safety we find in keeping these things in the realm of the possible. Harboring a belief in what we could be ensures that we never have to confront what we may not be. Gay Hendricks outlines this well in his book The Big Leap:

“Each of us has an inner thermostat setting that determines how much love, success, and creativity we allow ourselves to enjoy. When we exceed our inner thermostat setting, we will often do something to sabotage ourselves, causing us to drop back into the old, familiar zone where we feel secure…

Unfortunately, our thermostat setting usually gets programmed in early childhood, before we can think for ourselves. Once programmed, our Upper Limit thermostat setting holds us back from enjoying all the love, financial abundance, and creativity that’s rightfully ours. It keeps us in our Zone of Competence or at best our Zone of Excellence. It prevents us from living in the ultimate destination of the journey—our Zone of Genius.”

He’s talking about our comfort zone. This was the second criteria in picking a resolution candidate – what is realistic. The implication is clear, we need to look towards expanding this comfort zone on the upside. And that means that we need to turn up the heat by doing the hard thing. Eat the frog as author Brian Tracey advises.

2) The ultimate identity

All this talk of pain and possibility and comfort zones is really about change. And as bestselling books on habit formation, like Atomic Habits, have underscored identity is key to making new behaviors stick. Hendricks is telling us to challenge identities that are limiting. Our murder mystery might very well be a problem of mistaken identity instead – we didn’t adopt the identity that served us best.

If I could change only one thing in my early life it would be related to understanding of how malleable identity can be. Like most people, I had a short list of things I knew I was good at and others that I wasn’t. What I didn’t fully realize is that there were things in my comfort zone, that I identified with, and things outside it, that I didn’t. These lists kept me confined to my identity most of the time with motivation sometimes pushing me out of it. Rather than being someone who is good at drawing, or sports, or school, or something very context dependent, I’d adopt the identity based on character. For example, someone who is good at learning and improving, who does hard things, who is gritty, who pushes themselves, etc.

3) Conclusion: Forget the 4-Hour Workweek, Focus on 4%

At some level, this is what Carol Dweck is talking about in Mindset, Angela Duckworth in Grit, Jordan Peterson evokes this often, especially when he recounts the tale of Abraham from the Old Testament in We Who Wrestle With God. Or Jocko Willink in Discipline Equals Freedom. The list is endless. When Steven Pressfield urges us to overcome Resistance in The War of Art, he’s telling us to shout-down the voice that would keep us comfortable. Moving past Resistance is the gateway to the flow-sates that Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi studied intensively – he noticed that top performers got that way by being comfortable being uncomfortable. Challenges just out of reach, around 4% above our current capacities, resulted in full engagement and exponential progress.

So, the bottom line is be among the top 4% who actually make resolutions stick need not be better than 96% of people, just be willing to work 4% harder. Have a goal (for motivation), but the ultimate resolution should be to be consistent, to commit to push ourselves out of our comfort zone on a regular basis and focus on the actions. Progress no matter how small is progress. We are all fighting against entropy, just get the direction right. Quash the voice that artificially set an upper limit. Most objectives are health objectives, but the muscle we really need to flex to reach them – or any objective for that matter – is to kick ourselves in the ass and just do it. This year, regardless of the objective, keep the words of Seneca top-of-mind:

‘It is not because things are difficult that we do not dare, it is because we do not dare that they are difficult.’

K. Wilkins is the author of:

Stoic Virtues Journal: Your Guide to Becoming the Person You Aspire to Be

Rules for Living Journal: Life Advice Based On the Words and Wisdom of Jordan B. Peterson