Searching for meaning

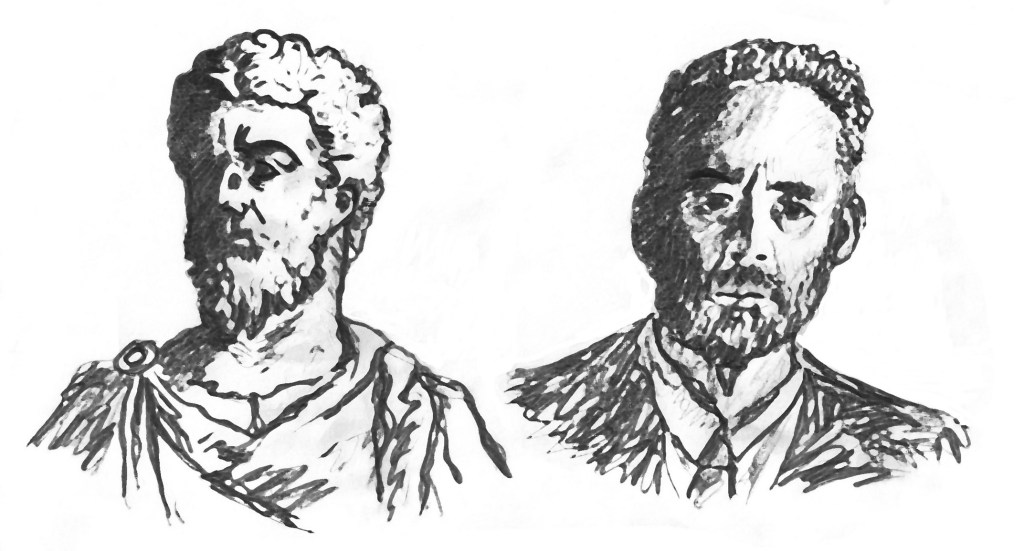

The divergent points of view of the existentialists and the Stoics on the nature of our suffering show that over two millennia the theory regarding the cause of the dis-ease has changed, but the medicine remains essentially the same.

In an age where half the population never reads for pleasure, and fewer still for learning, one would never predict that a university professor could turn his lectures into an international roadshow, filling auditoriums to deliver what is essentially the same thing he did in classrooms – a lecture on psychology, the Bible, mythology, philosophy, and neuroscience. With over 6 million books sold and over 15 million followers on social media, Jordan Peterson has built a substantial following; he is arguably the most famous psychologist in the world at the moment. In the span of only six years he has become one of the most preeminent public intellectuals of our time by peddling the last thing you would think anyone, especially the young people that tune-in the most, wants more of: rules and responsibility.

For over twenty years I’ve had a copy of Seneca’s Epistles in the drawer of my bedside table. A book that led me to the entire Stoic canon. As much as I cherish my entire collection of Stoic treatises, the last thing I would have imagined decades ago would be a surge in popularity of these ancient philosophical texts. Over the span of less than a decade, popular writers on Stoic philosophy such as Ryan Holiday have sold over three million books outlining the ancient philosophy. Podcasters such as Tim Ferriss have promoted it. Numerous other authors such as Donald Robertson, William B. Irvine, and Massimo Pigliucci, have joined the list of public figures promulgating the philosophy through books, articles, and courses. I recently read a statistic that something like a book a day is being published on this ancient chool of thought. The Stoicism thread on Reddit now has over half a million subscribers and scores of websites and blogs dedicated to the Stoics and have sprouted on the web. Within a culture where we tend to overshare vacation highlights and publicize and document each expensive dinnerplate, one would predict that the modern (and bastardized) version of the rival Epicurean school would hold more sway than the bear-and-forebear Stoics.

The two phenomenon are, in my mind, inextricably linked. I say this despite the fact that I have never heard Peterson quote Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, or Epictetus. I don’t even think I’ve heard him make reference to the Stoics or laud the school as a valid philosophy for modern times. Peterson himself cites the existential psychologists of the last century as having a significant influence on his thought. The writings and lessons from Frankl, Fromm, and May, to name a few of existentialists, bear much resemblance to his. Although he branches out significantly from there, his rules for living are an admixture that also includes the lessons of mythology, literature, and pioneering psychologists such as Jung and philosophers such as Nietzsche.

The lack of direct influence of the Stoics and Peterson would make it easy to dismiss their concurrent rise in popularity as mere coincidence, after all, correlation does not infer causality. The temptation to dissociate the concurrent rise in popularity of Peterson and Stoicism is even higher when one considers how importantly some of the underlying premises of each school of thought differ. The Stoics emerged in a time where people had a more fatalistic view of life. A slave and an emperor are among its greatest proponents, the slave not bemoaning his fate and the emperor refusing to see himself as superior to others; each dutifully accepted their allotted social roles. To a Stoic, meaning ultimately comes from the pursuit of wisdom and virtue rather than striving for pleasure or peace of mind. And the crowning virtue was justice. Thus, meaning is inherent in nature, which had an element of the divine in it, we are here to be of service to others. The existentialists, on the other hand, saw our challenge not to adapt to our fate, but to live with the anxiety that comes from we have none whatsoever; we are condemned to be free and tasked with giving meaning to lives that are essentially meaningless.

It’s difficult to believe that philosophies built upon such fundamentally divergent axioms about the nature of our life and suffering could offer advice on how to live well and conquer our troubles that could resonate in any way. However, to focus only on whether life is or is not inherently meaningful would be to obsess over the cause of a disease at the expense of the cure. The cancer patient cares much less over whether their tumor is the result of random exposure to cosmic radiation or from one too many medical x-rays: they want the operation that will extract the malignant mass. It is for this reason that Man’s Search for Meaning by the existential psychologist Viktor Frankl is a perennial best seller while the works by existential philosophers lag far behind. The public, people facing the task of living well, are looking for practical solutions instead of musings about the source of the problem. We look to Stoicism for the same reasons. What we learn in our obligatory Philosophy 101 courses bears little resemblance to the lessons of the ancient practice. Trolley problems are interesting, however they would be a trivial matter to an ancient Stoic. Marcus Aurelius illustrates this pragmatic and straightforward approach to philosophy when he reminds himself to “Waste no more time arguing about what a good man should be. Be one.” The Stoics were much more interested in rules for living. They were the psychologists of their day – physicians of the soul. In the words of Epicurus, “A philosopher’s school, is a doctor’s surgery.” (Discourses 3.23.30)

It is therefore not surprising that successful modern psychological therapies such as Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy (CBT) derives its origins from the ancient Stoics. The precursor to CBT, Rational

Emotive Behavioral Therapy (REBT), was developed by psychologists Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck around the same time that existential psychology was emerging. Ellis wrote that the central principle of his approach, that people are rarely emotionally affected by external events but rather by their thinking about such events. In other words, it is the meaning we ascribe to things that makes all the difference. It sounds a lot like Epictetus “We cannot choose our external circumstances, but we can always choose how we respond to them.” Who sounds eerily like Frankl: “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Frankl’s celebrated line has a heightened significance when one reads it in full context, describing the noble prisoners of concentration camps that maintained their character and even grew it in the most horrible of situations. Frankl continues:

“Every day, every hour, offered the opportunity to make a decision, a decision which determined whether you would or would not submit to those powers which threatened to rob you of your very self, your inner freedom; which determined whether or not you would become the plaything of circumstance, renouncing freedom and dignity…”

This emphasis on choice, and response, regardless of the circumstance harkens Epictetus: “Not even God has the power to break my freedom of choice.” The Stoics may have believed in fate, but they were not fatalistic. Their approach was not one of passive resignation, rather, it was one steeped in responsibility, while we must accept the things that are not up to us, our response is always in our command; it’s up to us to shape our characters and our lives. As Nassim Taleb has succinctly stated, “A Stoic is a Buddhist with attitude, one who says ‘fuck you’ to fate.” Likewise, Peterson continually reminds us that much of life is tragic, our response to it defines us. It behooves us to bolster our ability to weather the storms that inevitably come. He recommends, “aim to be the person at your father’s funeral that everyone, in their grief and misery, can rely on.” He finishes the statement with a line that one could easily have mistaken as something lifted directly from one of Seneca’s letters: “There’s a worthy and noble ambition: strength in the face of adversity.”

While their may not be a direct link between Peterson and the Stoics, there is a common thread.

John Vervaeke states in his new YouTube series After Socrates that the famous Athenian could be

considered the patron saint of the Stoics, “Stoicism is the religious philosophy or the philosophical

religion of internalizing Socrates.” The reverence of Socrates is no more evident than in Seneca’s

embodiment of his predecessor in his forced suicide. The heavy emphasis that Peterson places on

defining one’s personal values and the examined life – knowing where you’ve been, where you are, and where you are going – which is essentially an inquiry into the values that motivate your actions – harks back to the Delphic ‘know thyself’ mantra that Socrates argued so passionately in favour of. Know thyself is also about knowing your value – to the end of increasing it – which is a message that Peterson stresses continually: “We’re pack animals, beasts of burden. We must bear a load, to justify our miserable existence.” A third and not insignificant aspect of the famous dictum comes from Solzhenitsyn, another source of Peterson’s psychological insights: “”Know thyself!” There is nothing that so aids and assists the awakening of omniscience within us as insistent thoughts about one’s own transgressions, errors, mistakes.” Both, the Stoics and Peterson regularly come back to this theme of forthrightly recognizing your lesser instincts so to bring out your higher self. Above all, the Stoics, like Peterson, and Socrates, are fiercely dedicated to the truth.

Solzhenitsyn’s observations on good and evil also lead us to more common ground. Peterson is known for coming to the defense of religion for the values they impart upon us, Christianity in particular. Stoicism exerted an important influence on the ethics that underpin Christianity. Like Stoicism, Christian theology emphasizes character over material possessions. The cardinal virtues of

Christianity – prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance – have an obvious overlap with those of the Stoics. Stoicism may be so popular because it offers the opportunity to adhere to a set of values without the religious overtones or any sentiment that one has fallen under the spell of superstition or dogma. Through Socrates, and through Christianity, we see that what the Stoics were influenced by and what they influenced, all shaped Peterson’s message. This is not surprising, Peterson himself readily acknowledges that the wisdom he shares is a distillation of the wisdom that thousands of years of documented history offers us. All told, the divergent points of view of the existentialists and the Stoics on the nature of our suffering show that over two millennia the theory regarding the cause of the dis-ease has changed, but the medicine remains essentially the same.

Purpose, or meaning is the medicine both schools prescribe. Frankl expresses the fundamental

importance of meaning as an antidote to our suffering mathematically: D=S-M. “Despair (D) is essentially suffering without meaning.” Peterson picks-up on this theme, “The purpose of life, as far as I can tell… is to find a mode of being that’s so meaningful that the fact that life is suffering is no longer relevant.” As we saw, the precise prescription for finding meaning to a Stoic would be cultivating one’s virtues, it is a philosophy of eudaimonia, meaning very roughly ‘flourishing.’ Peterson advises: “And you might say, what’s the right way of being in the world? If there is such a thing. And it’s not acting according to a set of rules, it’s attempting to transcend the flawed thing that you currently are. And what’s so interesting about that is that the meaning of life is to be found in that pursuit.” Or, as Frankl advises, regardless of our situation, people are responsible “for making someone or something out of themselves.” Shunning expedient pleasures in favour of doing purposeful activities (Do what is meaningful, not what is expedient, one of Peterson’s rules for life), that lead to eudaimonic joy is embodied by this journal entry by Marcus Aurelius:

“So you were born to feel ‘nice’? Instead of doings things and experiencing them? Don’t

you see the plants, the birds, the ants and spiders and bees going about their individual

tasks, putting the world in order, as best they can? And you’re not willing to do your job

as a human being? Why aren’t you running to do what your nature demands?”

The quote simultaneously demonstrates another point where the existential psychologists, perhaps because they focus more on practice rather than theory, have more in common with their Stoic predecessors than existential philosophers. They dismiss the question of what is the meaning of life and focus on what is the meaning of your life. As Frankl says:

“Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather must

recognize that it is he who is asked. In a word, each man is questioned by life; and he can

only answer to life by answering for his own life; to life he can only respond by being

responsible.”

Like the Stoics, to the existential psychologist, meaning is uncovered rather than invented – as Frankl says, “You don’t create your mission in life – you detect it.” He asked his patients who found

themselves in the depths of despair and on the verge of giving up on life not to ask what they want from life, rather what life wants of them. Peterson is bringing the same message to modern audiences. He calls upon us to pay attention and find where we can make a meaningful contribution, telling us that “Interest is a spirit beckoning from the unknown.” He echoes Frankl again on the salavation to be found in persevering so to find your place: “Just because you don’t see your potential doesn’t mean it’s not there. Everyone has something to contribute, even if they don’t know it. You can always commit suicide tomorrow. Today, you have things to do. The world needs you even if you don’t need it.”

Marcus’ entry, ‘running to do what your nature demands,’ is also a call to responsibility, as a Stoic, our primary job as a human being is to be of service to others. Peterson also preaches for responsibility over hedonistic pleasure: “It’s in responsibility that most people find the meaning that sustains them through life. It’s not in happiness. It’s not in impulsive pleasure.” Politicians and national leaders have appeared on Peterson’s podcast; with such similarities in their views on life, it would be easy to imagine him interviewing the philosopher-king and getting along famously.

If the Stoics were alive today and were to write their own version of 12 Rules for Life, it’s not hard to imagine how it would resemble the popular modern treatise in many respects. If Peterson were to cruise the Agoras of antiquity in his toga and sandals, would his brand of philosophy be considered a rival school, or a branch or complement to the popular Stoic school? And you, as a plebian (a common citizen) strolling through the square searching for a doctor for your soul, would you not be equally tempted to see what the buzz is all about at the Stoa Poikile (Painted Porch) and why people are also gathering at the Peterson Academy?

Could it be that both schools offer an antidote to B.S.?

K. Wilkins is the author of:

Stoic Virtues Journal: Your Guide to Becoming the Person You Aspire to Be

Rules for Living Journal: Life Advice Based On the Words and Wisdom of Jordan B. Peterson